10. The Unsinkable Titanic

Sometime prior to March 19, 1912, Murdoch was appointed Chief Officer of the Titanic, and on the night of the 19th or 20th, accompanied by First Officer Charles Lightoller and Second Officer Davy Blair, left for Belfast in the midnight hours. They were, according to Lightoller, three "very contented chaps". Lightoller courageous, arrogant, duplicitous and witty will from this date tower over the Titanic story by virtue of staying alive: one of the advantages of a sole surviving eyewitness. A man of passionate attachments, entirely religious, Lightoller's testimony will reflect his sure and certain knowledge that his own escape from the Titanic was an Act of God (God had to get Lightoller alive off the Titanic as Lightoller had to be there, 28 years in the future, at Dunkirk, to save from the Nazis 131 men who in 1912 had not yet been born). One with God is always a majority, and from April 15, 1912, Lightoller will be impervious to the consensus of the United States Senate or any other earthly authority.

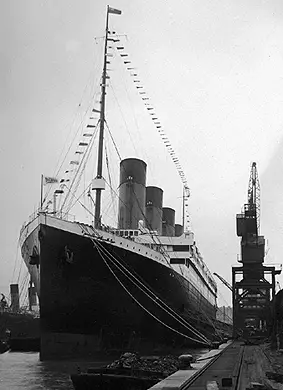

Unlike others who in years to come would report pricklings of unease when they first saw the Titanic, none of her senior officers sensed anything undefinable watching them board. Margaret Murdoch was certain that none of them was other than elated at the good fortune which had assigned them to Britain's most elegant ship. First Class passenger Edith Rosenbaum (Russell), boarding at Cherbourg, would survey the glittering interior and, with the sixth sense of a professional survivor, know that something was wrong: to the woman who had already avoided death by fire, automobile collisions, and the Johnstown Flood, and who would go on to sail serenely through the Blitz, the Titanic had all the warmth of a crypt. In direct contrast, Lightoller, writing in 1935, remembered her with undiminished awe. Decades after foundering, she lived in his memory as first seen, moored at Harland & Wolff's Thompson Graving Dock on a winter's morning.

Titanic dressed in flags for Good Friday

(April 5, 1912) in Southampton.

(Click image to enlarge)

The Titanic was a ship of light, all white and black and gold and glimmering brass, the sunlight sparkling on her long, englassed promenade. She was also the largest, heaviest ship then afloat. At 882.6 feet, she was 73 feet longer than the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise of World War II, 141.1 feet longer than both the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau, and a mere 4.6 feet shorter than the Iowa class battleships, including the USS Missouri, retired in 1992. This was the ship that White Star thought needed sea trials of one day for her officers fully to command.

The Titanic was Harland & Wolff's most famous creation; as sole purveyors to the White Star Line, as well as builders for those who could pay its well earned price, its sprawling ship yards and thousands of employees functioned as an extension of the fertile, unsleeping, relentless will of its managing director, Thomas, Lord Pirrie, of whom the description "ruthless bastard" would be an understatement. Pirrie managed his empire in a manner unknown after his generation, and drove his builders and designers with the same ferocious determination he turned on himself. Under Pirrie's direction, Harland & Wolff labored with Nibelungen intensity to complete its orders. In the 1909 1910 fiscal year, besides work on the Olympic and Titanic, six other liners were launched; by June of 1910, the Yard was so overwhelmed that Pirrie had to sub contract the lovely Preussen to John Brown at Clydebank, even though by the end of 1910 Queen's Island employed 11,389 men as opposed to 5,785 the previous year. (Most of them were frantically working to complete Olympic and hurry Titanic along.) By the end of the 1910 1911 fiscal year, Harland & Wolff had delivered 9 ships, including the Olympic, and accepted orders for 12 more. In addition to Titanic in 1912, six other ships were completed, and preparations went forward for the third of White Star's planned great liners, Britannic. It was a self produced situation in which it would be easy for desperately overworked men to forget something, or to assume amid the ungentle rush that information had been proffered when it had not.

The actual building of Titanic was under the direction of Thomas Andrews, Lord Pirrie's nephew, of whom it was assumed, on unspecified evidence, that Pirrie was fond. Unlike his uncle, Andrews was a man of warmth and great dignity, his brilliance diffused by kindness; he was the man of everyone's confidences, intimate and arbiter of all anxieties. He had neither vices nor enemies and his life was subsumed with his ships. To Andrews, the Titanic was not inanimate: as Athena from the head of Zeus, she had emerged alive from his mind.

No human child ever had a father more attentive to detail, more lavish with care, more careful against possible calamity, than the Titanic had in Andrews. He had tried to do the impossible: foresee everything. Had he, therefore, come to assume her invulnerability?

The non sinkable ship theory, like the Loch Ness Monster, kept surfacing regardless of logic. Not only did some marine writers hale Titanic as "practically unsinkable", others had said the same in 1909 of the Waratah, praising her double bottom and watertight compartments; she vanished on her second homeward voyage. Lightoller made mock of the notion of an "unsinkable ship", although it is unclear whether he felt that way in 1912 as well as in 1935, but many an intelligent man clung to the belief. The Imperial Japanese Navy felt that the battleship Yamato was unsinkable, right up to the day she sank in 1944, 32 years after the Titanic.

Since 1912, the feeling has been that the British Inquiry on the Titanic, conducted by the Board of Trade into its own regulations, resembled Lady Macbeth: "Woe, alas, what, in our house?" In reality, Members of Parliament and the Board of Trade knew about the inadequate lifeboat accommodation on every ship afloat. The emphasis, however, was on continual subdivision of ships' hulls with watertight doors and frequent bulkheads, in the apparent belief that an icecube tray with a superstructure would never go down; by this reasoning, more lifeboats, presumably, would become as superfluous as sails. (Cunard's Lusitania, as an auxiliary cruiser, was fitted with longitudinal bulkheads, resulting in a chilling little paragraph in the Captain's Manual advising him to abandon ship if she ever adopted and held a 23 list: there are, after all, several ways to sink. Nobody worried about that, either, except, presumably, the captain of the Lusitania.)

Whatever Andrews' own belief, his stunned incredulity on the night of April 14th suggests that while he may not have felt that she could not sink, he had thought that she would not. His confidence was infelicitous and infectious and shared by Titanic's crew, almost to a man. Fireman W. H. Taylor:

Mr. Taylor: A majority of them [crew] did not realize that she would sink.

Senator Newlands: Was that ship regarded by the crew as an unsinkable ship?

Mr. Taylor: So they thought.

. . . . .

Senator Newlands: Regarding these great iron ships, with watertight compartments, that is the general feeling among the seamen, is it?

Mr. Taylor: Yes, sir.

Senator Newlands: They feel safe on them?

Mr. Taylor: Yes.

Senator Newlands: Even although [sic] there are not enough boats to accommodate all the crew and passengers?

Mr. Taylor: Yes, sir. (Page 557)

Taylor had been ordered to man No. 15 by Murdoch. When he boarded the lifeboat, he felt that it was still merely a precaution, that they were evacuating passengers not because there was an emergency but because there might be one. (Page 558) Taylor only changed his mind after No. 15 was rowed clear and he saw the Titanic down by her bow: seeing is believing. Only seeing, it would appear, was believing that night -- even for those who should have known better. Lightoller did not grasp that the Titanic would actually founder until shortly before she did, when he looked down a forward crew stairwell and saw the North Atlantic a few decks down looking back at him.