6. Conditions at Sea

The high regard is remarkable considering the conditions prevailing in the passenger trade. Lightoller in his memoirs (The Titanic and Other Ships, 1935) stated disengenuously that unlike the Royal Navy the merchant marine did not need its captains' authority reinforced by King's Regulations; he might have added, not, anyway, when the British Merchant Shipping Act of 1894 and a variety of United States statutes would suffice. Passengers who exclaimed over White Star's gleaming salons and staterooms did not see the world below decks where firemen, stokers, and engineers kept up the steam that provided all the comfort and power hundreds of badly paid, hard worked, ferociously disciplined men, who, like the poor everywhere in that age, generally came to the notice of the high born and well dowered only when their behavior provoked trouble.

If Murdoch was personally insulated from the worst of the era's laboring conditions, he was not unaware of them. On October 11, 1905, the liner Oceanic arrived in Liverpool from New York, and 33 of her firemen were promptly arrested for "conspiring to disobey" the captain's orders during the voyage. The disagreement had arisen over wages, the men purportedly had refused to work, and all were sentenced to a week's imprisonment at hard labor the next day, October 12th. Murdoch as one of Oceanic's senior officers would have been involved.

Captain Smith and officers on a Sunday morning

inspection of RMS Adriatic

In January of 1907, there had been a brief, threatened strike against White Star by checkers, over a reduction in their pay. In May of 1907, Adriatic, with Murdoch as her First Officer and E. J. Smith as Captain, arrived in New York on her maiden voyage, in the midst of one of the most violent of all East Coast dock strikes. White Star's piers were under guard, and strikebreakers were hired to load the Adriatic for her return trip; not, however, the Italian strikebreakers who had quit one week earlier when White Star had refused to honor its promise to let them have Sunday off. The company also declined to send them home by water, as agreed; the men had to brave the howling mob beyond the dock area, which made every effort to kill them. This incident had occurred a few days before the Adriatic at that time the world's largest and most luxurious new liner arrived with the company chairman, J. Bruce Ismay, aboard. Ismay, personally a considerate man who appreciated his employees, nevertheless stated to the press after a brief onboard meeting with American White Star officials that he saw no reason to change company policy on treatment of dock workers; if he had an opinion on the double cross of the Italian workers, he did not share it with the New York Times. Murdoch's view of company policy cannot be known, but he would certainly have been apprised of the past week's events, and was obliged to load the Adriatic with men desperate to support their families whose lives were being threatened by other badly used men on the far side of the sheds. She sailed on time, back to Britain where White Star seamen and firemen had struck over the company's refusal to grant a wage increase of ten shillings ($2.50) a month.

The men had still not been granted the $2.50 per month demand on August 8, 1910, when over 100 firemen walked off the Adriatic the night before she was scheduled to depart for New York, insisting upon the ten shilling increase and, additionally, being paid for extra work already performed. White Star's use of strikebreakers had become more clever since 1907, and on August 9, 1910, the Adriatic left the line's heavily guarded Southampton piers punctually at noon; office clerks had been sent below to get up steam, and at the Isle of Wight and again at Queenstown newly hired stokers were taken aboard. Nearly 50 of this scratch crew deserted once in New York, a matter about which, among other complaints of the National Sailors' and Firemen's Union, White Star officials were unavailable for comment.

White Star would finally grant the extra $2.50 a month in 1911, four years after the initial demand. This time it was the new Olympic, loading for her maiden voyage, which was struck. On June 10, 1911, the crew walked off and the next day the company offered wages equal to those Cunard paid its men on the Lusitania and Mauritania. Perhaps company officials intended a conciliatory gesture for Coronation Year. The Olympic sailed on time, but by then the most violent strike of all was raging, on both sides of the Atlantic. The demand was now $5.00 a month; White Star granted half that, and in Southampton trouble was largely avoided. But in Liverpool, the Celtic was under guard, dockers and carriers supported the seamen, and shipowners retaliated with a lockout; there were riots, fires, strikes in more ports, and thousands of irate stranded Americans. The Government sent in the Army as the United Kingdom faced serious shortages of food and fuel (the New York Times proposed famine as a real possibility) and the Royal Scots Greys moved supplies in Liverpool while Home Secretary Winston Churchill denied that there had been volley firing on strikers by troops. In New York, the British Consul warned British seamen they would be jailed if they refused to board ship, and more than one non striking crew held off strikers or their union delegates with firehoses. In the end, the men, their families facing destitution, generally went back on the shipping lines' terms.

White Star's treatment of its employees was ruthless, like the times, and tragedy would not distract its attention from the bottom line. Those who survived the Titanic would find their pay calculated to 2:20 am, April 15th; when the sea closed over her stern, the men who lived were off the payroll. As for those who died, and whose heirs attempted to collect compensation, the company's solicitors made every effort to evade payment: in one case, publicized by Mark Sullivan in October, 1912, in Colliers, compensation was denied the mother of a deceased steward by adding in the purported value of meals to bring his salary above the statutory minimum. (The company felt it had been sufficiently gracious by not suing his estate for the loss of White Star funds entrusted to him to provide change for passengers.) A shilling unescorted did not get by White Star's accountants; regulations forbade crew members to carry any purchases home without paying the relevant shipping fee, and passengers "obtaining coal from the cook to throw at sharks" had to reimburse the company at the market price for coal, an example of meanmindedness probably unequaled anywhere outside Dickens.

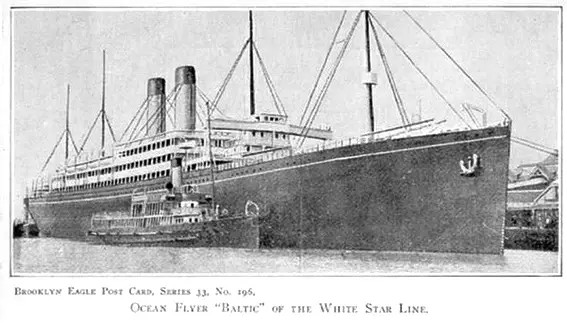

RMS Baltic (1904 - 1933).

White Star's ruthlessness extended to more than money: the company required silence, and if necessary untruth, in the event of accident. In an era where ship design was pushing into the unknown, wireless was just leaving the toy stage and electricity was still supplemented by oil, lacking sure navigational aids, and with minimum legal restraints on owners, or at least their agents, collisions and groundings were not unexceptionable, but they were disquieting to a public becoming ever more insistent upon corporate accountability and less patient with risk. White Star's settled solution, should mishaps occur, was to require of its officers and men as much denial as could be managed. Two examples, both involving the Baltic, are eloquent testimonial to the extent this policy could be made to stretch.

The Baltic had a history of running into things (the State of New Jersey, mostly), and on June 30, 1910, she collided with the German Petroleum Company's tanker Standard in mid ocean in the middle of the night. The Baltic limped into New York, where irate passengers disembarking on July 5th reported to the New York Times that they had been told almost nothing, merely bland assurances that the damage was not great; officers and crew had been forbidden by the captain to discuss the accident, and the wireless operator had been instructed to transmit nothing from which the public could infer that a collision had even taken place. The press release handed to reporters upon docking was smoothly uninformative, and White Star officials were not pleased to discover that someone, somehow, had got a full report to the New York Times, which had published it on July 4th, 1910; copies of the Times tossed up to passengers from the press boat provided them the first adequate account of the accident.

A year prior to the Standard collision, the Baltic had run aground twice entering New York, first in the Swash Channel in May, and then on November 23, 1909, in a fog, she had slammed into the New Jersey shore. Scores of members of a local volunteer life saving society had run onto the beach, in case of need, and had stayed until it was clear the Baltic could be floated free. The story was on Page 1 of the New York Times and the next day, November 24, 1909, page 2 carried the denial by Baltic's officers that she had grounded; it was, they demurred, some other ship that had done so (and then cut in front of the incoming Mauritania, after regaining the channel). How so many people, waiting by the ship for over an hour, could have been so mistaken as to her identity was not explained by White Star.