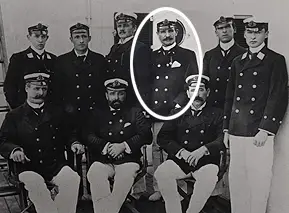

4. A Portrait

Crew of the Medic in Melbourne, Murdoch

in the centre, with Lightoller to his right (taller).

(Click image to enlarge)

The first surviving photograph of William Murdoch was taken in 1902 on the Medic, apparently in Australia; it shows a relaxed young man, age 28 or 29, sporting a splendid mustache which no doubt required a good bit of attention, handsome in summer uniform. Murdoch was the ship's First Officer, and standing to his right is Charles Herbert Lightoller, the Second Officer. Lightoller has struck a pose reminiscent of that favored by prize fighters of the era. Murdoch, the military cut of his uniform jacket relieved by a perfectly folded white handkerchief and what appears to be a fob on a chain, is much more poised. He seems to be the only man in the picture enjoying the moment.

Chief Officer James McGiffin is seated in front of Murdoch and to the far left. In 1912 McGiffin was White Star's Marine Superintendent at Queenstown and would come aboard the Titanic on April 11th to speak briefly with two old friends. What was said is unknown, but McGiffin, apprised of disaster by telephone on the morning of April 15th, would leave White Star's service forthwith and in a rage. He had been especially fond of Murdoch had, in fact, once hoped to be his brother in law and all his life would keep a menu printed for some officers' dinner in 1900 on the Medic which Murdoch had autographed for him:

Whatever obstacles control,

Go on, true heart, thou'lt reach the goal.

What the quotation meant to either party is not knowable. Perhaps it was appropriate to whatever the conversation may have been at that long gone dinner party. What is certain is that it is one of the few glimpses of William Murdoch offered directly, by himself.

The young officer who looks steadily at the viewer in the Medic photograph was already in good fortune the man he would be in tragedy. At that August, 1912, Dalbeattie public meeting, the Rev. J. A. Paton of the United Free Church Manse stated "he had always been struck with Mr. Murdoch's courteous, brave and unassuming manner". The Kirkcudbrightshire Advertizer preferred "imperative" and "self controlled". The long training in sail, the influence of family history, the austere traditions of the Church of Scotland, in all of which duty and honor were exactly defined, had produced a character forthright, unwavering, unfragile. Noted for extremely even temperament and charm of manner, in Murdoch the formal courtesies of the age, reinforced by the necessities of life at sea, overlay a total absence of moral uncertainty and the poise of rank. He had come to mirror in his own person the virtues of his culture and time, and can be named in a word as archaic as the Age of Empire he inhabited: impavid.

Those who knew Murdoch, who had served with him or under him, generally emphasized his composure when testifying in the American Titanic inquiry the essence of the stiff upper lip tradition. Murdoch had behaved exactly as expected of a British officer in a tight corner, and surviving crew members wanted that fact published.

United States Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce, Titanic Disaster Inquiry, transcript, page 549:

Senator Newlands: Is there any particular point that you would like to speak of, or anything in regard to the collision that you know that you think you ought to tell?

Mr. Wheelton [First Class Steward]: I would like to say something about the bravery exhibited by the first officer, Mr. Murdock. He was perfectly cool and very calm.

Senator Newlands: And he was lost?

Wheelton: Yes, sir; he was lost.

Wheelton had never before served in the merchant marine, having joined the Titanic after 16 years in the Royal Navy. The majority of the crew, like the passengers, generally believed the ship would not sink. Murdoch knew otherwise:

Senator Newlands: Was there anything like a panic on board the ship?

Mr. Hardy. [Chief Steward, Second Class]: Not at all, because everybody had full confidence that the ship would float.

Senator Fletcher: Up to what time; up to the time your boat left?

Hardy: Up to the time my boat left. She began to list before we left her.

Senator Fletcher: People even then thought she would float?

Hardy: Of course I had great respect and great regard for Chief Officer Murdock, and I was walking along the deck forward with him, and he said, 'I believe she is gone, Hardy'; and that is the only time I thought she might sink; when he said that."

(Senate Inquiry, Page 591)

Hardy went on to inform Senator Fletcher that despite Murdoch's warning, despite the sinister tilt of the deck as his boat was lowered, he "still had confidence the thing would float, though, sir, without a doubt." (Page 592)

Third Officer Thomas Pitman agreed with Hardy. Ordered by Murdoch to assume charge of the second starboard boat launched, his departure was formal, its intent obvious. Pitman, however, was too anxious about being adrift in the North Atlantic to catch Murdoch's meaning:

Mr. Pitman: So Murdock said, 'You go in charge of this boat.' [No. 5]

Senator Smith: Murdock said that to you?

Pitman: Yes; he said, 'You go away in this boat, old man, and hang around the after gangway.' I did not like the idea of going away at all, because I thought I was better off on the ship.

Smith: That is, these passengers thought so or you thought so?

Pitman: I thought so.

Smith: You thought they were better off on the ship?

Pitman: I thought I was.

. . . . .

Pitman: He said, 'You go ahead in this boat, and hand [sic] around the after gangway.' He shook hands with me and said, 'Good by; good luck;' and I said, 'Lower away.'

Smith: Murdock did?

Pitman: Murdock shook hands good by, and said 'Good luck to you.'

Smith: Did you ever see him after that?

Pitman: Never. . . .

. . . . .

Smith: When you shook hands with Murdock and bade him good bye, did you ever expect to see him again?

Pitman: Certainly; I did.

Smith: Do you think, from his manner, he ever expected to see you again?

Pitman: Apparently not. I expected to get back to the ship again, perhaps two or three hours afterwards.

Smith: But he, from his manner, did not expect that?

Pitman: Apparently not. (Pages 277 278, 282)

The discipline that the crew so admired was imposed by will power, by fearful single mindedness, on a warmly emotional nature. The few glimpses into his mind that survive, the charm of the only existing letters, the sporadic illuminating word from Titanic survivors, suggest considerable feeling just beneath the practiced composure. Murdoch belonged to a culture that eschews all public displays of emotion, regardless of circumstance; hence Wheelton's praise, and Hardy's memory of a classic specimen of British understatement. Murdoch knew that the world's greatest oceanliner was going to founder, knew, moreover, that only a fraction of her company would be alive at dawn; absent a rescue ship alongside (statistically, even with one) those who did not drown would soon die of exposure. He could as a deck officer assume command of a lifeboat for the very real purpose of safeguarding passengers in mid Atlantic; by regulation, he was in any event assigned to command one. Unlike others, William Murdoch had a choice between life and death: his obligation to stay with the Titanic was exclusively moral. By remaining at his post, to the bitter end, he had, like Iphigenia at Aulis, chosen the honor due intangibles over his own life.

Captain Smith and Olympic's senior officers.

Murdoch stands to the left, a little detached from the main group.

(Click image to enlarge)

The photograph of Murdoch alone on Titanic's bridge (generally used by publishers) should perhaps be less favored in considering what he actually looked like in 1912, nearing middle age; he appears severe but shadows indicate he faced the sun and was merely uncomfortable. Usually described as "tall" (crew members, passengers) and sometimes as "large", "powerful" (the Kirkcudbrightshire Advertizer) Murdoch followed his family pattern: well built, broad shouldered, commanding presence, chestnut hair, hazel eyes. In the words of the last family member who knew him, he stood "six foot plus". As his brother Samuel was 6'1", it is possible, but Murdoch appears to be 5'10" or 5'11" in most photographs, suggesting the extra inches were an illusion created by military bearing and force of personality.

A formal studio photograph taken in September of 1907 shows a handsome man still quite young, somewhat slimmer than in 1902, serene, beautifully dressed, with a hint of humor. The mustache is now dignified rather than exuberant; by the next known photograph, taken in 1910 or 1911 on the Adriatic (published in the Titanic Historical Society magazine in 1987), it would be gone. There would be little change between 1907 and 1912. His cool, autumnal elegance seems to match that of the Titanic herself, and perfectly accords with the necessities of classical drama: no one sympathizes with an ugly victim.